The Skinny:

The exit cap is one of the most important assumptions in any real estate underwriting, it is also mostly nonsense. While it is important to be able to intelligently estimate the exit cap, it is far more important to focus on investments where its impact is made irrelevant.

What is the Exit Cap Rate?

In commercial real estate, most of a deal’s total return (e.g. IRR) is driven by appreciation as opposed to its income. This is just true by the nature of the asset, remember real estate assets are not bonds! Obviously this means that the price you sell a property for should be meaningfully higher than your all-in cost basis (purchase price + upgrade costs).

There are only two ways to ensure that your exit value is higher than your entry value. First, you can increase the cash flow your property generates through a combination of (i) increasing revenues and (ii) decreasing expenses. Second, you can hope the broader market will value your property more at the sale than you did at your purchase, all else equal. The exit cap rate is what drives the latter.

As detailed in this post, the cap rate is both a simple and intricate metric that is primarily used as a comparative valuation tool. It reflects the stabilized pricing that buyers and sellers are willing to transact at for a particular type of deal in a particular type of market. The cap rate is driven by a whole host of factors that includes economic conditions, capital flows, and interest rates. Therefore, the exit cap rate is a forecast (aka speculation) that estimates where the market will be transacting at many years out into the future.

For example, if your specialty is Class A apartment buildings on Trantor and you know firsthand that the market cap rate is 5.0% today, the exit cap rate simply seeks to answer the question: “what is the market willing to pay for this building when I plan to sell?”

Why the Exit Cap Rate is BS

You can probably tell by the definition and my tone why it is BS. It is essentially a multivariate forecast of the local and world economy! If anyone was adept at forecasting that, they would either be the richest person in the history of the world or they would be Hari Seldon.

One of the first things every real estate investor needs to truly accept in their heart and mind is that they have no idea what the exit cap rate will be. It simply cannot be accurately predicted. It could be well above, well below, or the exact same as the entry cap rate.

On the other hand, the exit cap rate plays a key role in determining future appreciation, which as mentioned earlier, plays the lead role in driving the total return. Said differently, it is one of the most sensitive assumptions in your underwriting (along with rent growth).

This is the other main reason it is BS, because it can be manipulated to make any deal look acceptable. It can turn poo into diamonds. All you have to do is write some fluffy rationale to convince yourself that it is not overly aggressive. Tightening the exit cap downwards a smidge might not seem like a big deal on paper (and plenty of investors would not notice) but it has a massive impact.

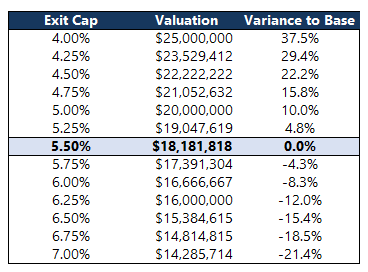

Review the chart below to see how a value can change with 25bp increments using a $1mm NOI. I would recommend memorizing the % impact cap rate changes can bring.

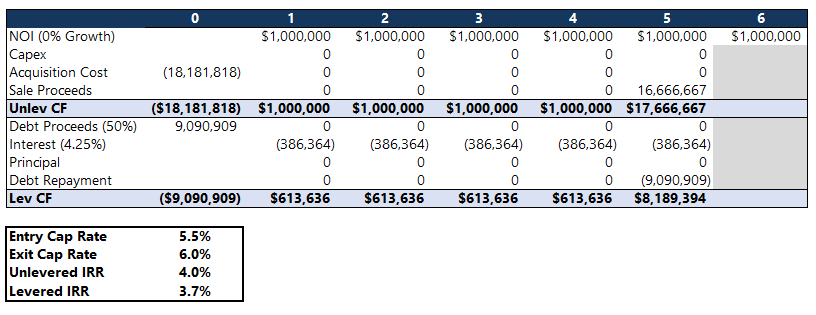

If we hold NOI constant, we can really see the impact this can have on your projected returns and whether or not your investors will be pissed or not.

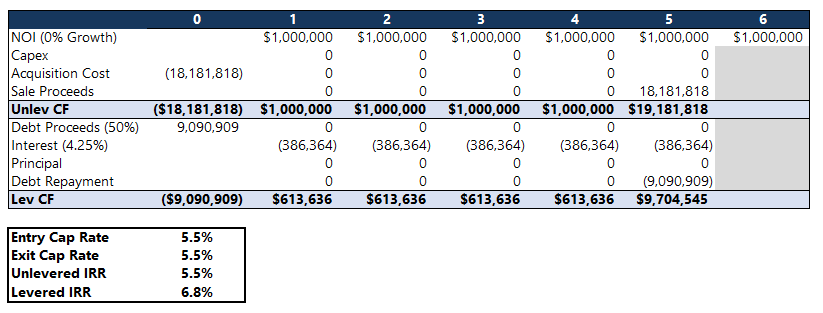

Let’s say you tell your investors you feel strongly that cap rates will not move in the 5 year expected holding period and that they should expect an IRR of ~7% with conservative leverage.

But as the economy is wont to do, conditions change and tighten up so the market cap rates shift 50bp upward (not at all unlikely over 5 years) which causes your exit value to be 8.3% below your entry value…

Well great job, your net return is lower than your lender’s, and your investor could have probably done better buying risk-free treasuries. Sure it was not your fault that the economy changed for the worse, who could have predicted that? Either way it does not matter and mistakes like these are a pretty fast way to never raise capital from the same investor group again.

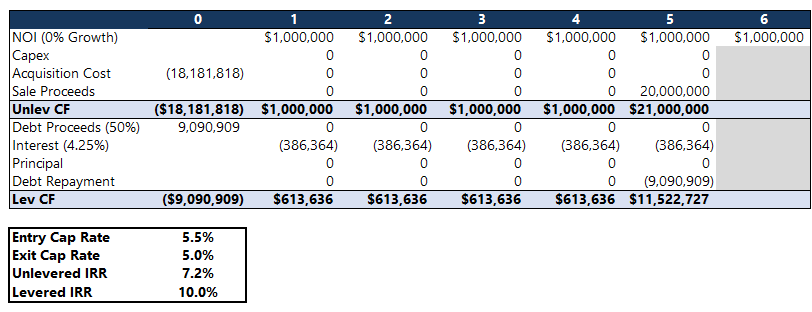

But what if you surprise to the upside and your exit cap is lower by 50bp?

Are you a genius? A hero? You might feel that way if you beat your projected return by 300bp or nearly 50%. In fact, many inexperienced operators did feel this way in the recent pandemic-induced real estate boom. However, a sharp investor would immediately call you out and say that you had zero part in driving that return (NOI is still the same) and that your success was entirely reliant on non-controllable market conditions.

If this seems like a lose / tie situation, that is because it is. This is what you get for being passive instead of active and cautious. That is why the exit cap rate is BS, it is a lever in an underwriting that the buyer has no control over.

How to Make the Exit Cap Rate Irrelevant

As mentioned earlier, there are two ways to increase your exit value: increase the NOI or hope that the exit cap rate compresses. The former is active and the latter is passive. In order to make the exit cap rate irrelevant (aka less impactful) a real estate operator needs to focus squarely on what they can actively control to increase NOI. This is usually achieved through value-add projects such as renovations and improved operations.

This is so important because it allows you to shine as an operator while protecting your downside and opening up the upside. If you are laser focused on driving NOI growth through improvements, you do not have to sweat about what the broader market is doing. You are creating value from nothing and are “forcing” appreciation without relying on favorable market trends as a crutch. Said differently, there are no Hail Mary’s in your playbook.

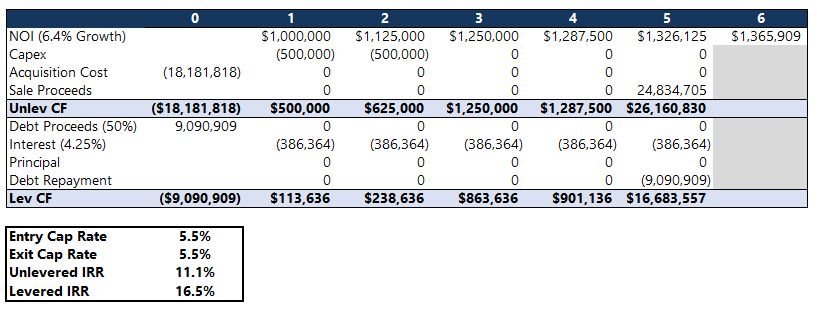

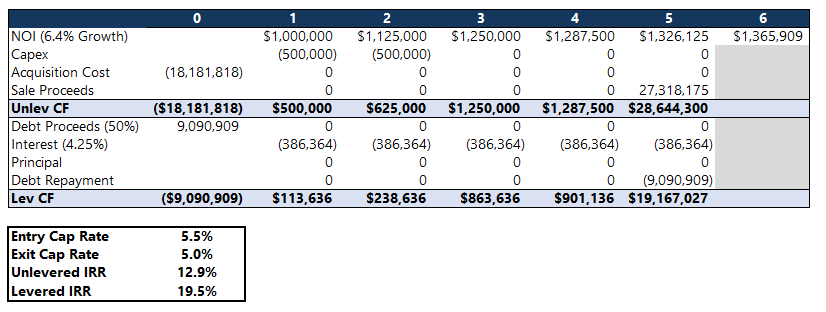

Let’s assume you are able increase the Year 1 NOI of $1mm to $1.25mm by Year 3 through a comprehensive repositioning program. This will allow you to earn an NOI CAGR of 6.4% over the holding period. The capital expenditures required are $1mm and it will take you 2 years to complete.

Your base case is a very strong 16.5% net IRR, plenty of investors will sign up for that.

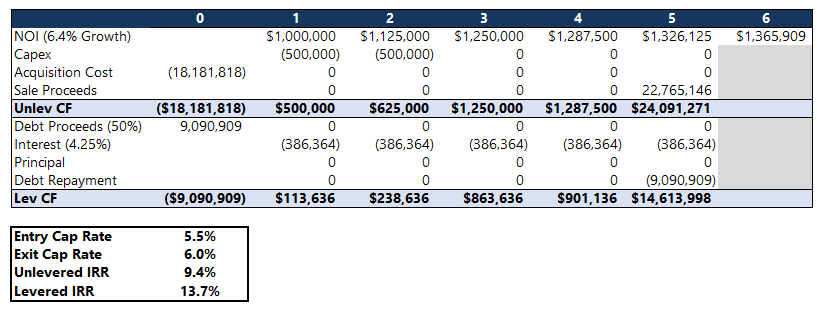

Your downside case of a 50bp cap rate expansion brings you a still attractive 13.7% net IRR. Trust me, your investors will not be upset about this! While they will definitely remember an expected 13% going to a 7%, they will not sweat over an expected 16.5% going to a 13.7%, both are outsized and desirable.

Your upside case kicks ass with a whopping ~20% IRR, the holy grail return threshold of private equity real estate. If you achieve this, your investors would be thrilled and will give you big pats on the back, but you would humbly shrug and say “we got lucky with the market timing” because as a true real estate operator, you only take credit for things you made happen directly.

4 Ways to Estimate the Exit Cap Rate

Even though the exit cap rate is BS, you still need it for your underwriting, so here are the 4 methods I recommend utilizing to back up your assumptions and to avoid the temptation of using whatever number makes the deal work.

The most important thing is to be conservative but realistic. Being overly conservative can artificially dissuade you from buying good deals, so you should not just assume the exit cap rate will be way higher than your entry. Fortunately, cap rates have stayed in a general “band” historically so you have some built in rails to guide you as to what is appropriate and realistic.

Here are the four methods I recommend:

- Simple Expansion Heuristic

- Change in WACC and Growth

- Spread over Treasuries

- Utilize Replacement Cost

Method #1 – Simple Expansion Heuristic

Using a simple expansion heuristic is my go to. All you need to do for this is take today’s market cap rate (not a property’s in-place cap rate, that is irrelevant!) and increase it by a certain amount of basis points per year of your holding period, typically 5-10bp.

So if today’s market cap rate is 5.0% and you plan to hold a property for 5 years, your exit cap rate will be 5.25% (5.0% +.05%*5) or 5.50% (5.0% +.10%*5). Generally if you are in a blue chip gateway market you can get away with using the 5bp but for most places 10bp is probably a safer assumption. Again, refer to historical cap rate fluctuations as a guide.

I love this method because it matches the inherent arbitrariness of the exit cap assumption with an equally arbitrary estimation technique. It is a tacit admission that you have no idea what it will be, but that you would like to be conservative by showing a measured expansion.

Keep in mind that your entry and exit cap rate should be decided somewhat independently of one another. For example, if you bought a 3 year old Class A apartment building, that is still considered a “newly built” core deal at acquisition and deserving of the appropriate lower cap rate. However, in a 5 year hold that building is going to become a bit outmoded and might slide down to a Class B (riskier) profile.

So in this case, if Class A market caps are 5% when you buy while Class B market caps are 5.25%, and you want to assume a 5bp / year expansion, your exit cap rate needs to be 5.50% (5.25% + .05%*5) not 5.25% (5.0% + .05%*5) in order to account for this change in profile.

On the other hand, if you are buying a Class B deal that you are renovating into a Class A building, you would key your exit cap off Class A and show an exit cap of 5.25% not 5.50%, again accounting for the change in profile.

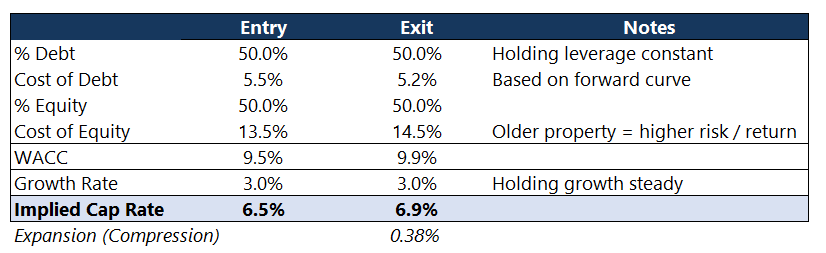

Method #2 – Change in WACC and Growth

As outlined in this post about cap rates, the formula behind the cap rate is:

Cap Rate = Required Rate of Return – Expected Growth Rate

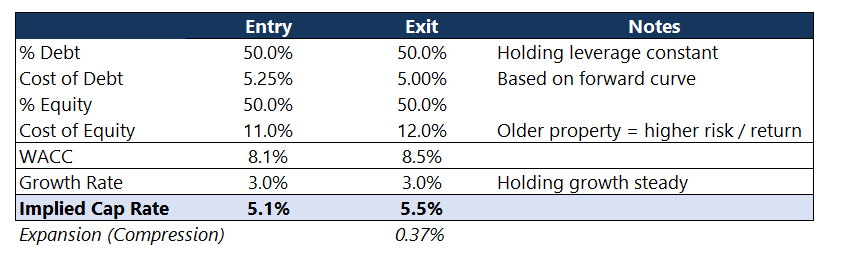

The required rate of return is just the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) between the debt and equity investors. We can use this to make thoughtful (but again, speculative) predictions for where cap rates will move to.

Here is what that quick analysis looks like:

The issue with this technique is that there are a few big time assumptions. First, you have to assume that the capital structure remains constant, otherwise you can skew your WACC lower by assuming a higher debt load. Second, you have to predict interest rates and credit conditions since index rates and spreads underpin the cost of debt. The forward curve on websites like Chatham are directionally helpful, but they are often ultimately off. Finally, you have to assume what new equity investors will want to earn. This is probably the least presumptive of the inputs because you know that the property will be older upon a sale and therefore riskier and deserving of a higher return.

So basically while this is a good way to break down your exit cap assumption, all of its inputs are speculative, again demonstrating how it is all shenanigans.

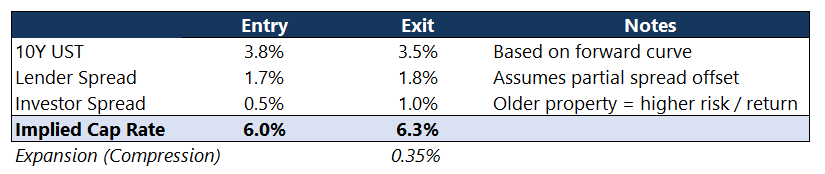

Method #3 – Spread over Treasuries

Cap rates are often compared directly to treasuries, just as corporate bonds are. While I firmly believe that this is an unfair apples to oranges comparison (because cap rates and bond yields are income measures, but real estate provides hefty capital appreciation while bonds do not), it is still helpful to compare them nonetheless because there is historical data to draw from.

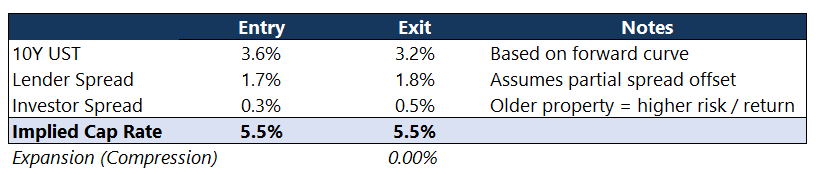

Historically, the relationship between multifamily cap rates and 10Y treasuries is about 2.0-2.5% but this of course varies by location, asset quality, and economic conditions. This also makes sense intuitively because you almost always want your cap rate to be higher than your loan interest rate (positive leverage) and your loan rate is based off of the risk-free treasuries (UST + lender spread + equity investor spread ≈ cap rate). Cap rates are often compared directly to BB corporate bonds (spreads of ~200bp) for their similarities in risk profile (although again, apples to oranges).

So you can use a forward curve and historical spreads to get a rough estimate of the exit cap rate:

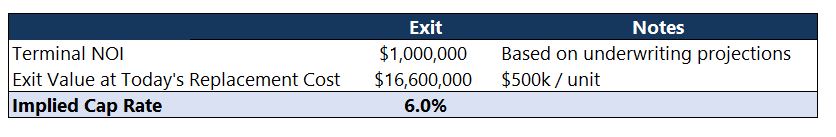

Method #4 – Utilize Replacement Cost

This method takes a completely different approach that does not factor in the highly unstable capital markets predictions. When you are buying a piece of real estate, you generally want to buy below replacement cost, because that is a built-in hedge to new supply.

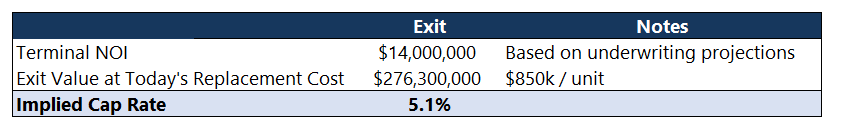

Since this is desirable trait for new buyers, we can make some assumptions and back into a cap rate without the need to project debt and equity costs. Let’s assume that the terminal / exit NOI in a 5Y hold is $1mm. Current replacement costs for your asset type are $500k / unit. If a buyer can buy in 5 years at today’s replacement costs, that should be desirable and can help round out your estimate.

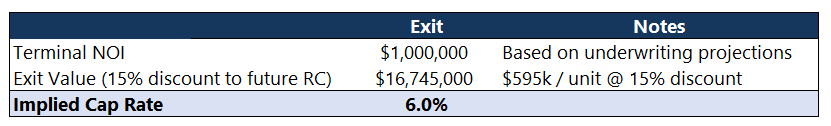

Note that another way of running this is to grow replacement cost by a reasonable cost inflation amount (3-4%) and then assume a new buyer will want to buy at X% discount to replacement cost (say 10-20%). Here is how that would look like if we grow replacement costs by 3.5% per year and assume a future buyer wants to acquire at a 15% to replacement cost:

Sample Exit Cap Rate Analysis

Let’s put this all together in a real life example using the assumptions below:

Assumptions:

Holding Period: 5 Years

Today’s Market Cap Rate: 5.0%

Cap Rate Expansion Per Year: .05%

Equity Costs: 11% today, 12% in 5Y

Debt Costs: 5.25% today, 5.0% in 5Y

Lender Spreads: 1.7% today, 1.8% in 5Y

Capital Structure: 50/50

Steady State Growth: 3.0%

Replacement Cost: $850k today, $1mm in 5Y (15% discount target)

Exit NOI: $14,000,000

Method #1 – Simple Expansion Heuristic

Exit Cap Rate = Market Cap Rate * Expansion / Year * Holding Period

Exit Cap Rate = 5.0% * .05% * 5

Exit Cap Rate = 5.25%

Method #2 – Change in WACC and Growth

Exit Cap Rate = 5.50%

Method #3 – Spread over Treasuries

Exit Cap Rate = 5.50%

Method #4 – Utilize Replacement Cost

Exit Cap Rate = 5.1%

SUMMARY

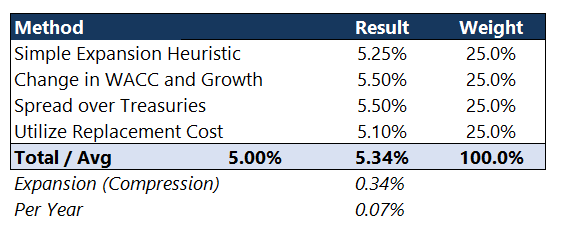

After you run each method, I would recommend summarizing them cleanly in a chart and weighting them based on your confidence level. In this case, the range is pretty clear and should give you a good base assumption for the exit cap.

Bonus Method – The “Re-Buy” Analysis

If you are feeling extra fancy, there is one more method you could run. This is called the “re-buy” analysis. This is where you take the role of a potential new buyer and underwrite it fully at a future point in time. If the sale date is January 2030, you would create a new underwriting model starting at this time.

This is more thorough because you get to truly price it as someone new would, and factor in costs of debt and determine a valuation based on required return metrics. I would be shocked if the result here is drastically different than the quick methods above, but if you have the time to run it you might as well do so.

Also worth noting that the re-buy analysis suffers from the same inherent flaws as the other methods. You still need to make some big assumptions like debt and equity costs, but you also now need to input future rent growth and other nebulous items so it is actually even more speculative.

Summary

The exit cap rate is a sensitive assumption that is difficult to predict because there are so many uncontrollable unknowns. These methods will help you dial in a defensible exit cap range, but you should accept that they might be way off. The key to mitigating this uncertainty is to buy deals that do well no matter where the exit cap lands, and you do this by focusing on the things you can control like disciplined entry price points, value add projects, and improved operations.