The Skinny:

The cap rate is both a very simple and a very complex number that is the most common and important valuation metric used in commercial real estate, understanding its uses and components is crucial.

The Plain English Definition:

The cap rate equals a property’s net operating income (NOI) divided by its purchase price. It reflects a basic potential rate of return on a real estate investment. It is both a simple metric and an intricate one, as it is also meant to capture the level of risk, return, and growth potential. Functionally, it is mostly used as a comparative measure when reviewing one or several deals.

Just as EBITDA multiples are ubiquitous in the traditional finance world, cap rates are their counterpart in the real estate world. NOI is the EBITDA of real estate. In fact, if you are making the transition from traditional finance, you can just take the inverse of the cap rate and turn it into a multiple if you want to ease your way in.

Cap Rate = NOI / Purchase Price

Generally a higher cap rate (lower multiple) is supposed to mean higher risk / return and a lower cap rate (higher multiple) lower risk / return, but I will explain later on why that is not always the case.

The Mathematical Definition:

You would be surprised at how many real estate professionals do not know (or do not appreciate) the underlying math behind the cap rate. Since it is used almost entirely as a comparative metric based on historical data (e.g. 10 similar deals in the market traded at a 5% cap rate recently, so the market cap rate must be 5%) no one really thinks about the math behind it. But what if you were dropped into a market that has no sales data? How would you determine an appropriate cap rate? That is where the math part comes in.

The formula behind the cap rate is below. If you took any finance courses, this should look familiar because it is indeed a direct relative of the famous Gordon Growth Model used in valuing (dividend-paying) stocks.

Cap Rate = Required Rate of Return – Expected Growth Rate

Required Rate of Return – the required rate of return is simply what you need this deal to earn you on a total return basis to make your investors happy. What is the correct required rate return? Well, that is simply another finance 101 concept, the WACC (weighted average cost of capital). If your equity / debt split is 50/50 and your equity needs to see a 14% return and your loan’s interest rate (aka your lender’s required rate of return) is 4%, your WACC is 9% (50%*14% + 50%*4%).

Expected Growth Rate – the expected growth rate is the constant and perpetual growth rate for the numerator (the NOI). In reality, you are thinking about the growth rate for the next decade-ish rather than infinity. 3% is the de facto starting point.

So continuing with a simple example, you have determined that your required rate of return is 9.0% and you believe that NOI will continue to increase at 3.0%. The appropriate cap rate for that investment would therefore be 6.0% (9% – 3%). If this does not match up with the asking price, you need to find out why. Maybe the Seller is asking too much or maybe you are getting a great deal!

Using the Cap Rate Components to Understand Markets and Deals:

For any investment, you should use these two levers to analyze the pricing and whether it makes sense or not based on its inherent risk / return characteristics. Think about it as a matrix with the four quadrants listed below. I have added sample calculations to illustrate how the levers work together.

High Required Rate of Return / High Growth – this would describe a market or deal that is viewed as having a lot of growth potential but with plenty of risk. Can you think of any markets that fit this? I can think of a few, especially in some of these alleged Covid boomtowns! Your equity and debt investors would need to be compensated with higher returns for the risk, even with the solid growth potential. Think of these as the shiny tech startups of the real estate world.

Required Rate of Return / WACC = 10%

Growth Rate = 5%

Appropriate Cap Rate = 10% – 5% = 5%

High Required Rate of Return / Low Growth – this would describe a market or deal that has the unfortunate combination of being risky and boring. If you have ever seen a listing for a deal in the Rust Belt over the past decade, you know what I am talking about. You might be initially lured in by the high cap rates, but as an educated investor you would know that there is a reason why they are so high. The debt is likely very expensive because lenders do not want to lend there and because there is minimal appreciation potential, your equity also needs a juicy return upfront via strong immediate yields. While many people make good money in lower quality markets and deals (e.g. Class C and below) they know what they are signing up for and that they are being compensated for risk, headaches, and potential value traps.

Required Rate of Return / WACC = 10%

Growth Rate = 1%

Appropriate Cap Rate = 10% – 1% = 9%

Low Required Rate of Return / High Growth – these are the darlings of the institutional investment world. They have blue-chip fundamentals, a strong and growing economy, and are the most desirable cities for many residents. Gateway markets such as New York, the Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Seattle are some examples that are considered “Tier-1” in institutional parlance. Lenders want to lend there and investors want to invest there, so the cost of capital is low. Also, because of their attractiveness, NOI growth will be continue to be strong. When you hear ridiculously low cap rates in a trade, it is usually in one of these markets.

Required Rate of Return / WACC = 8%

Growth Rate = 4%

Appropriate Cap Rate = 8% – 4% = 4%

Low Required Rate of Return / Low Growth – this would describe a market or deal that is both highly stable but without any real catalyst for future growth. These are typically secondary markets that likely have low vacancy but are close to their ceiling on rents. The comparable in the equities world would be the “slow-growers”, mature companies who do not really innovate that much anymore but that are consistently strong dividend payers (e.g. Coke, Colgate, 3M). I would place government leased office buildings in this category as well as other “back office” towns, both of which are usually boring and long-dated, but stable.

Required Rate of Return / WACC = 8%

Growth Rate = 1%

Appropriate Cap Rate = 8% – 1% = 7%

Cap Rates vs. the Risk Free Rate:

While I personally find the mathematical approach to be best way of thinking about appropriate cap rates, there is another simpler method that I like to refer to as well, and that is the “build-up” method.

The entire financial world is based on the risk free rate (U.S. Treasury Bonds or “USTs”) because it represents the best return you can get that is completely guaranteed. Therefore, literally every other investment needs to have a higher rate of return than UST’s. The build-up method is another finance 101 concept that is used to determine the appropriate return premium relative to the risk-free rate.

For equities, it would go something like this:

Cost of Equity = Risk Free Rate + Market Risk Premium + Industry & Company Specific Premiums

While it is impossible to say whether equities or real estate deserve a higher required rate of return (since it is totally specific to what is being compared), one thing we know for sure is that real estate has something that equities do not, illiquidity. Illiquidity is undesirable because everyone wants the comfort of knowing they can sell at fair market value in a pinch. You cannot do this with real estate and therefore investors deserve an illiquidity premium to compensate them.

The build-up method for real estate in terms of cap rates, can be simplified to the below:

Cap Rate = Risk Free Rate + Lender’s Spread + Investor Spread

A. Risk Free Rate – this is the baseline guaranteed return and is generally represented by the 10 Year UST in real estate. Let’s say this is 3.0% (although the average since 1960 is actually ~5.8%!).

B. Lender’s Spread – every single fixed-rate loan is priced relative to the risk free rate via a spread. A lender needs an incentive to earn more than guaranteed money of course. While spreads fluctuate based on market conditions, credit risk, and asset types, they generally stay within a predictable band. You will become fluent real quickly with spreads if you pay attention and should be able to estimate your own debt costs before you even talk to lenders. Let’s say their spread is 1.50%.

C. Investor’s Spread – so now we get to the equity investors, who are lower in seniority of course than the lender, so they will need an additional spread. Buying at cap rates (C) below the debt interest rate (A+B) is generally anathema (this is called negative leverage and is usually no bueno) so this should be positive. Let’s say the investor spread is 1.0%.

Appropriate Cap Rate = 3.0% + 1.50% + 1.00% = 5.50%

I said earlier I like to refer to this method, but that is it, I do not really use it in reality. It is more of just a fun sanity check. The main reason is that it is really an apples to oranges view. Real estate investments are not bonds, they are not only producing income, they are providing a huge chunk of returns from appreciation which is not captured here.

That is why when someone says “why would I buy real estate at a 5% cap rate if Treasuries are at 5%” you must metaphorically slap them with knowledge and remind them that real estate offers so much more than a baseline 5% income stream. It almost always offers increasing Y/Y yields, capital appreciation, and the opportunity to add real value through direct control.

I would of course love to buy every deal with immediately positive leverage, but that is just not possible all the time. If there is a deal that has a low initial cap rate but also has a very clear path to value creation and a killer IRR, that provides me with the comfort to accept the low cap rate. Said differently, if you know you can comfortably get to a 15% IRR, do you really care whether the cap rate is 5% or 6%? No, because as a real estate investor you are focused on the total return not just the yield metric.

Let’s see how the mathematical and build-up method play together:

Assumptions: Risk-free rate of 4%, lender spread of 2%, investor spread of 1%, equity required rate of return of 13%, 50% debt, 3% growth rate

Cap Rate (Math) = Required Rate of Return – Expected Growth Rate

Cap Rate (Math) = 50%*(4%+2%) + 50%*(13%) – 3%

Cap Rate (Math) = 6.50%

VS.

Cap Rate (Build-Up) = Risk Free Rate + Lender’s Spread + Investor Spread

Cap Rate (Build-Up) = 4% + 2% + 1%

Cap Rate (Build-Up) = 7.0%

Well the difference between the two is obviously not immaterial and could possibly be the difference between you winning and losing a deal. The build-up method is more conservative because it is essentially treating the equity investor as nothing more than a second-position lender without the beauteous bodacious upside provided via appreciation!

Two things can be true at once, strong immediate positive leverage is very desirable and should be secured whenever possible, but it should also not be a strict gating issue given there are two major sources of returns. Understand and utilize both methods and remember that each are just one of the many angles that you will look at in your analysis.

In-Place Cap Rates are USELESS:

Ok, not every in-place cap rate is useless, but most are. When referring to cap rates, you are generally referring to the “market” cap rate not the “in-place” cap rate. The market cap rate is for stabilized deals that fit a certain profile and reflects a valuation that buyers and sellers are willing to transact at. In-place cap rates on the other hand could mean literally anything.

For example, let’s say there is a $1mm deal for sale that has an in-place NOI of $25k. The in-place cap rate would therefore be 2.5% but the market cap rate is 6%. This deal stinks right! Well it certainly might, but what if you actually review the materials and see that the building is 50% vacant because it has just been fully renovated and all it needs is someone to lease-up the rest of the building? Furthermore, once it is leased, the NOI will be $70k and your in-place cap rate becomes a 7%. With a little bit of sweat equity to do the leasing, you can make a tidy profit (100bp spread to the 6% market cap or ~17% gain). As soon as you reviewed the deal, the in-place cap rate became irrelevant.

Cap Rates vs. IRR:

I have referenced several times here the importance of focusing on “total return”. Real estate is primarily a total return business, meaning it generates a return from both income and capital appreciation. The cap rate is really just an income focused metric, but IRR is the total return metric.

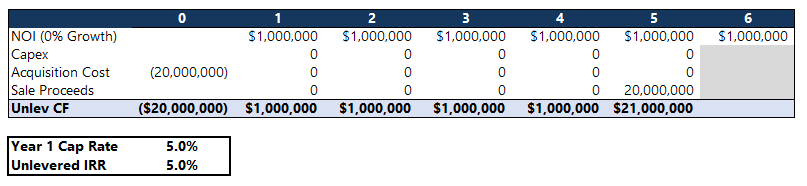

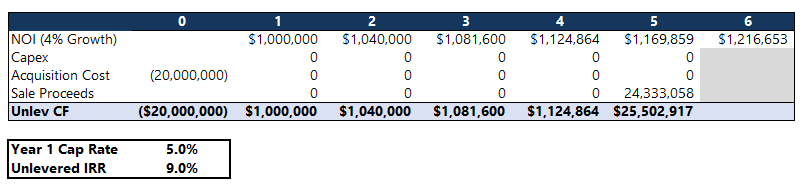

The IRR and cap rate actually have a fairly direct relationship. The (unlevered) IRR will actually equal the cap rate under a specific (and unlikely) set of assumptions. First, NOI cannot grow at all, it just stays the same throughout the analysis period. Second, there are no other cash outflows such as capital expenditures. Third, the exit price is the same as the entry price (and since NOI is the same, that means the exit cap rate is the same as your entry cap rate). Fourth, there are no sales / friction costs associated with the exit. This is illustrated in the sample 5 Year analysis below. In a way, you can think of the cap rate as your absolute minimum return if you do not use debt and do absolutely nothing operationally forever which can only be achieved by leasing long-term to Rip Van Winkle.

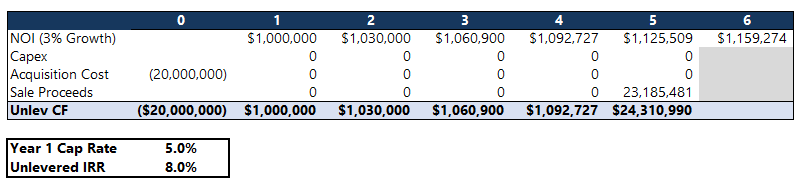

But what happens if we allow the analysis to get closer to reality? What if we say NOI will increase each year by 3%. Notice anything familiar?

What if we increase the NOI by 4% instead of 3%?

What you are once again seeing is the mathematical relationship between the required rate of return and the growth rate (IRR, WACC, and required rate of return are siblings of one another). Again, this is a simplified analysis with some unrealistic constraints, but I hope you find it useful when you think about what a cap rate represents.

Summary:

The cap rate is the most important metric in real estate for a reason. It is the one solo metric that can tell you a lot about a particular market or deal right away. While it is a simple calculation (NOI / purchase price), there is a deeper story behind it that is told by its two main “authors” (required rate of return and growth rate). It is important to think critically and comparatively about each in order to determine what the appropriate cap rate for a given opportunity should be.