The Skinny:

The framework and process to value a deal in real estate is the same for basically every single property. You must determine the following: (i) What is the stabilized value? (ii) What is the cost to get to that stabilized value? (iii) What is the appropriate profit margin for effort required?

The Components of a Real Estate Valuation:

When reviewing a potential acquisition, it is natural for new or overly-eager investors to want to immediately download all of the available information and plug it into their intricate models to see what the forecasted IRR and cash-on-cash metrics would be. While such heavier analyses have a place in the underwriting process, every deal must be distilled into its key components and reviewed in a simple manner first. This will ensure that you focus on what really matters in a deal without getting lost in the details. Once you do this a few dozen times, it will become second nature and you will know whether you like a deal well before you open your full underwriting model.

Every real estate deal has three components, summarized below, and the objective is to reach a valuation, or in the context of a potential acquisition, a “max bid”:

Stabilized Value – this is the value of the property after you have completed your business plan (if there is one). If it is a turnkey core deal, then the stabilized value is simply what the market value is today. However, if there is a value-add component such as interior or common area upgrades, then the stabilized value would be the market value if all upgrades were completed today (highly recommend keeping this “untrended” by using today’s rents!). This is the starting point of your analysis.

Cost to Reach Stabilized Value – this is the amount you need to spend to transform the property into the version that you are reflecting in your stabilized value. Again, if it is a turn-key core deal, this amount is $0 but if you need to spend additional dollars for upgrades, this would all be accounted for here. Note that many only include the “hard costs” in this line item, which are the actual capital expenditure dollars spent, I think a key “soft cost” item should be reflected here as well, which is is the time it takes to reach the stabilized value. I explain this in more detail later on.

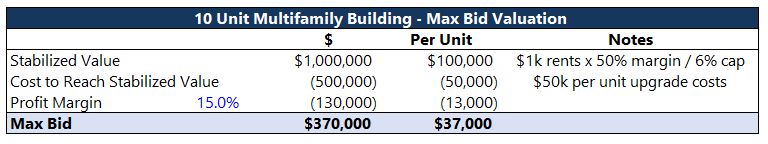

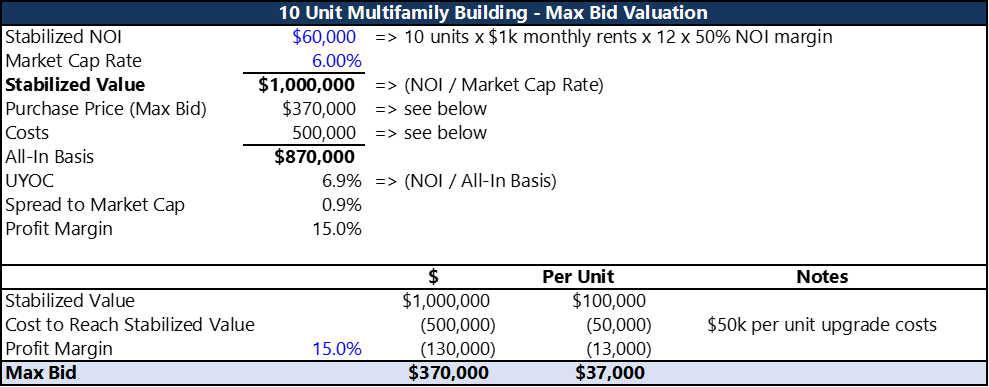

Profit Margin – while real estate is a very enjoyable business, we are all in it because it is both enjoyable and profitable. This is the line item where you need to factor in how much you deserve to make on the deal for bringing it to fruition. If the stabilized value for an apartment building is $1mm but it costs $500k in upgrades to get to that stabilized value, you will not be willing to pay $500k at acquisition because your profit would be $0. You deserve your “take” which should be commensurate with the risk. The functional effect of this will be to reduce the price you are willing to pay, and it essentially the plug number in the analysis. Continuing with a simple example, let’s say you believe a 15% profit margin is fair to get the property to be worth $1mm. Your max bid will need to be $1mm / 1.15 – $500k = $370k. You would sell for $1mm on an all-in basis of $870k.

Here is what this simple analysis should look like in your head, on the back of a napkin, or in a spreadsheet:

Importance of Using “Static” Metrics:

It personally took me way too long to appreciate the importance of simplified static valuations. I have always loved modeling and building intricate and elegant analyses and proudly walking my superiors through them. Now I know that they mostly ignored them because (i) they had already run the simplified analysis themselves and (ii) they were really only looking to make sure the intricate analysis agreed with their simplified one (if both are correct, they should always agree!).

Valuations that overemphasize projections are subject to a lot of potential bias, while static analyses are not. The two biggest culprits in a discounted cash flow / IRR analysis are the rent growth and exit cap rate. Both of these metrics can be manipulated in order to make any deal hit the required return. Rent growth is a powerful assumption that can make any deal look good because it is compounding. However, if the deal is reliant on outsized rent growth (e.g. greater than 2-3% / year) to make the numbers work, that leaves it very susceptible to the downside. It also does not do anything to improve your reputation as a savvy operator because it is totally out of your control.

The same goes for the terminal or exit cap rate. Most of a deal’s total return is driven by appreciation, so exit cap is especially crucial. The problem is the exit cap the most BS metric in real estate. It is a highly multifaceted metric driven by economic conditions, opportunity costs, capital flows, geography, and interest rates among others. If you could accurately forecast interest rates or cap rates, you would have more money than god and would not be reading this real estate blog.

The simplified technique eliminates all the potentially misleading levers from your valuation. While I still adore modeling as it is a true hobby, I only use my models nowadays for two reasons (i) to double check my simplified valuation and (ii) because your investors need to see the cash flow projections and IRR.

Now let’s take a deeper look at each component and walk through how to estimate them in a back of the envelope (“BOE”) manner as well as in a more detailed manner.

Component #1 – Stabilized Value:

Every property you buy has a business plan and the stabilized value is simply what it is worth if the business plan was successfully executed today (aka on an untrended basis). This is the starting point from which you deduct your costs and profit margin from in order to arrive at your max bid. A business plan could be simple (“our plan is to continue operating the building as a new Class A community”) or heavy (“we plan to buy this decrepit office building, demolish it, change the zoning, and build the world’s largest Chuck E. Cheese’s”). Here is how to arrive at the stabilized value:

Back of the Envelope – if you are fluent in the market you seek to buy in, you should know (i) what the rent range is for both brand new and older product (ii) the NOI margin and (iii) the market cap rate. This allows you to run this calculation very quickly. Choose a reasonable rent PSF number that you have triangulated (make sure it is annualized) multiply it by the NOI margin, and arrive at the stabilized NOI. Then simply divide this by the market cap rate to arrive at the stabilized value. If you do not know the rent range, NOI margin, or market cap rate, you are not ready to be buying in the area as you should first have a command of these key inputs.

I recommend using PSF rents instead of total rent amounts, as they are easier to think about it. For office / retail, this is standard anyways since suite sizes can vary massively. For apartments, PSF rents are how you think about market rents in practice. For example, if you are looking to renovate a 20 year old apartment building and you know that the average PSF rent is $4.00 for brand new product and $3.00 for 10 year old aging product, you should immediately know that your renovated PSF rents will fall between these two. Your understanding of the numbers will only compound as you do more deals, and the primary data you get from your own deals is very valuable to replicating a strategy.

Also please note that NOI margin has a few different definitions depending on the context. The textbook definition for NOI margin is NOI / EGI (EGI is gross rental rents + other income less vacancy and collection losses). For purposes of the BOE though, NOI / GPR (gross potential rent, which is the annual projected rent at 100% occupancy) should be used since it is easier for quick calculations. These two margin percentages are different so make sure you are using the right one at the appropriate time.

Detailed – arriving at a stabilized value using the detailed method is something that you will need to do at some point if it passes muster in the BOE. You should complete this pretty early on in the underwriting process. For this, you need to go line by line in the pro forma income statement to determine and memorialize your assumptions for every revenue and expense item. You will then arrive at your highly researched stabilized NOI number which you can then divide by the market cap rate to arrive at your stabilized value.

Component #2 – Cost to Reach the Stabilized Value:

The stabilized value is the destination, but the journey to get there is the cost. Any investment that is not “turnkey” or “core” has costs that need to be quantified. For development, it is a very multifaceted process involving land, hard costs / improvements, soft costs, and carry costs. For core-plus / value-add it is more straightforward and typically involves PSF or per unit renovation costs and common area amenities costs. Here is how to arrive at the cost to reach the stabilized value:

Back of the Envelope – if you are in tune with your market or have direct operational experience there, then this will be simple. For apartments, you should be able to look at the photos and say something like “yeah, these units are in rough shape, it probably needs $30k / unit to get to the rents we are targeting” or “these units are in great shape, they only need a few things here and there, let’s put down $10k / unit”. For office properties, the estimate will be much rougher because you could have some suites that are in new condition while others may look like they could have housed Gordon Gekko. Still, there should be a rough PSF number that you feel comfortable using as a plug, say $100 PSF. Common area, exterior work, and amenities upgrades are all bespoke but I recommend using a healthy plug number by slapping an additional per unit or PSF cost in the budget. For example, in addition to the $30k / unit renovation costs, add another $5k per unit if the common areas need some work. Same thing goes for PSF costs for offices. The accuracy could range from very accurate to way off, so always err on the conservative side. Much more fun to tune down capex numbers later than to increase them and try to make up for it elsewhere.

Detailed – I firmly believe that every team should have a pure-play construction expert in-house or a trustworthy third party on speed dial. Preferably, these individuals will have a wealth of experience working in different building types and construction scopes, from full developments to light rehab. They will have war stories from different economic cycles with a seemingly magical ability to spot minor and major issues immediately. They are also a great communicator and translator between the contractors and vendors. They must love their job (construction) as much as you love yours (acquisitions, AM, capital markets).

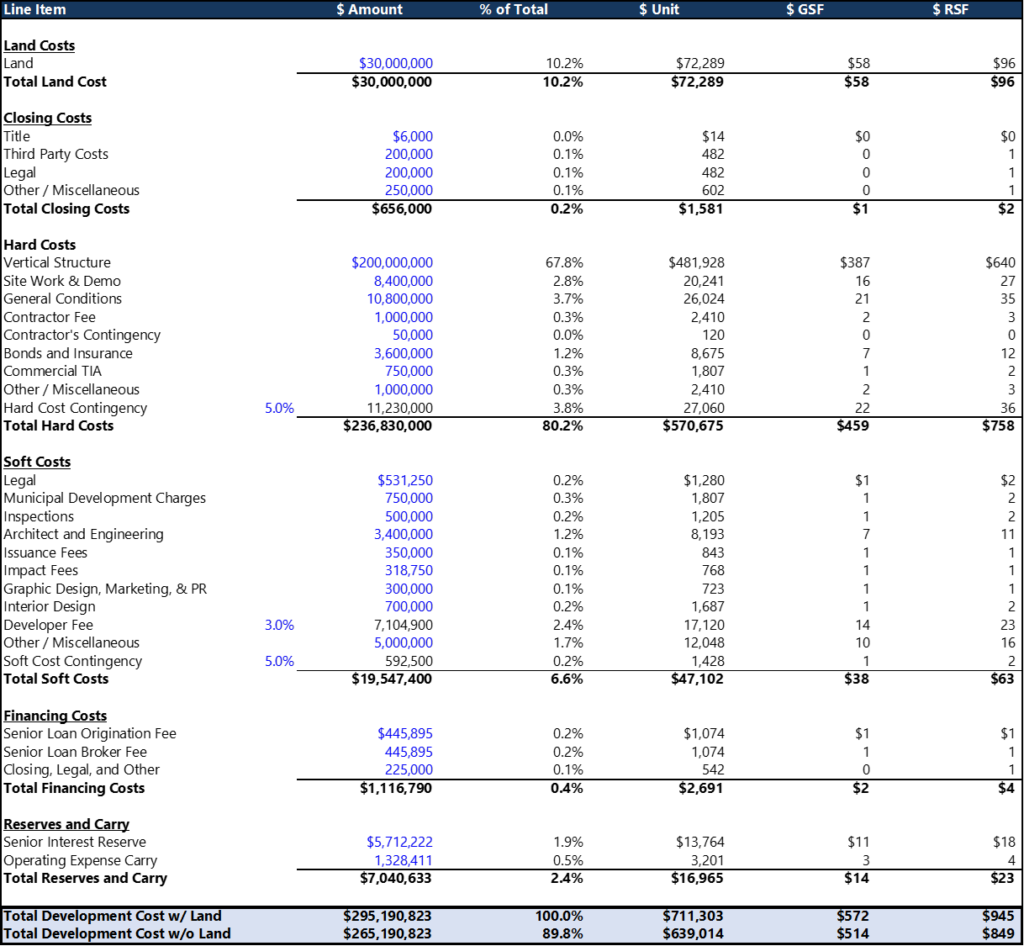

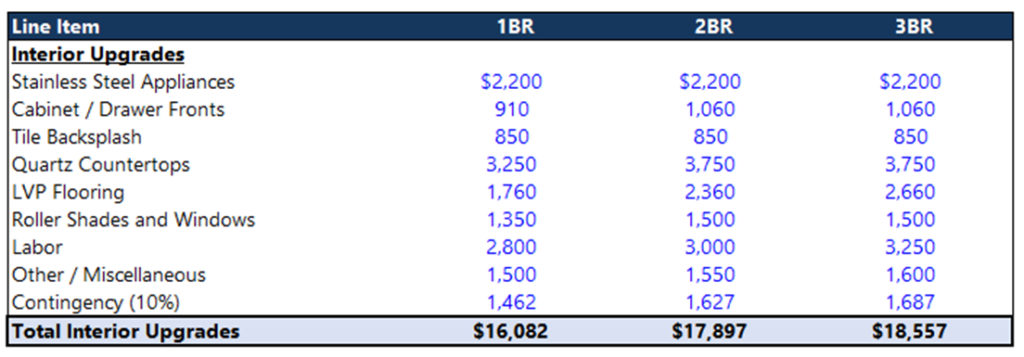

In conjunction with this construction rock star, you must take the time to prepare a meticulous budget for the scope that you and your team have determined for the business plan. Costs at this stage are no longer speculative and the “big ticket” items therefore must be backed up with several bids (at least 3!). Property Condition Reports and other third-party reports will help guide this process. Below are sample budgets for a development (simplified a bit) and a value-add multifamily project. Notice the difference in complexity. Always, always add in a juicy contingency of at least 5-10%.

Sample Budget #1 – High-Rise Apartment Development

Sample Budget #2 – Value-Add Apartment Repositioning

Component #3 – Profit Margin:

Like any successful venture or investment, you need to be properly compensated for efforts that take on risk and add value. Profits underpin and drive every enterprise, because none of them would keep at it if their bank accounts showed goose eggs month after month. Fortunately, there are plenty of profits to be made in real estate.

In the context of real estate valuation, the profit margin refers specifically to the return on investment of your value-add efforts. By its very nature, the stabilized value (aka market value) already prices in some expected rate of return reflected by the market cap rate. But if you are putting in additional capital to create additional value, a return must be factored in because no one wants to put in hard work for nothing in return. For core / turnkey deals, additional costs are $0 and therefore there is no additional profit margin to factor in, you will simply accept the market rate of return. Note however that if you can buy a core deal below its market value, you are awesome at your job and your profit margin / compensation is that spread (which you deserve by being a savvy deal-maker).

For properties where you are truly creating value, you need a real return. As Heath Ledger’s Joker said in “The Dark Knight”: if you are good at something, never do it for free. Developers do not build a development for $1mm and sell it at $1mm. They seek (and deserve) a juicy margin of 20-30% on their total cost and for the endless headaches the process causes. Similarly, value-add apartment investors will not pay $300k / unit, spend $25k / unit in upgrades, and then sell at $325k / unit. They will seek a return of 10-15% on their total costs. The return via the profit margin must be commensurate with the risk undertaken. The profit margin serves as the “plug” that determines your max bid.

Relationship to Cap Rates / Yield Spreads:

Many savvy investors in the real estate community focus on the UYOC to market cap spread. This is totally fine (I am a fan of anyone who emphasizes using static untrended metrics). The Untrended Yield on Cost (UYOC) is the stabilized NOI (after renovations with today’s untrended market rents) divided by the all-in costs to get there (acquisitions costs + renovation costs). They will often seek a UYOC that is 100-200bp above the market cap rate for their investments. This is their way of calculating profit margin. If market caps in an area are 7% and they can buy and renovate a property for an UYOC of 8.5%, that is a 150bp spread and a profit margin of ~21%.

This approach is very closely related to the method outlined in this post, except for one difference: yield spreads can mean totally different things in different markets and economic cycles. Let’s say you are an investor who seeks out a 150bp spread to market cap rates as your investing rule. The deal in the previous paragraph would work for you. But let’s say this same investor was presented a killer opportunity in a growing gateway market with inherently lower cap rates. The numbers indicate the property could be purchased and upgraded with an UYOC of 5.5% and sold for the market cap rate of 4.5%. The spread is a paltry 100bp at face value, so it is a pass right? Wrong! The profit margin is ~22%, which is great and higher than the other deal above! If the investor stuck blindly to their rule and filtered this out of the buybox list, a great opportunity would be missed.

Using a straight profit margin “standardizes” this potential bias no matter what the cap rates or UYOC’s are. Please see below for how the two analyses link together.

Sample Valuations:

To illustrate these calculations, I am using the same valuation process for three types of projects. For the sake of the illustration, I am also going to assume that the end product (and therefore the stabilized value) is the exact same. Imagine that each is on an identical plot of land and when the business plans are complete, they would all look identical.

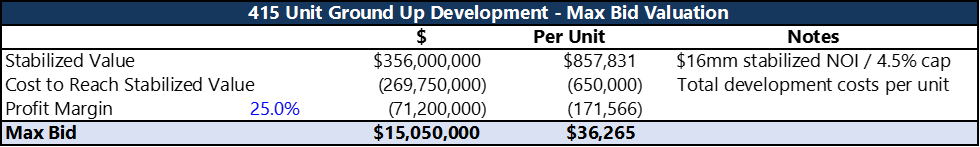

Example #1 – Ground-Up Multifamily Development

Since this is a ground-up development, the max bid is the amount you would be willing to pay for the land. The stabilized value is what the building would be worth if it was built and fully leased today. The cost to reach stabilized value equals the build costs (excluding the land) or quite literally the replacement cost. This number includes hard costs, soft costs, and carrying costs. The profit margin is nice and big at 25% because the multi-year and multifaceted development process is only worth it for the profits it can bring. There is a reason so many industry titans are real estate developers!

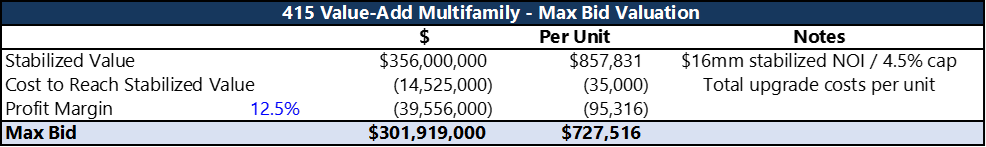

Example #2 – Value-Add Multifamily Repositioning

In this example, the building might be 5-15 years old. It was a blue-chip building when it was built but now it is cosmetically outdated. It needs $30k / unit for interior upgrades and $5k per unit in exterior and amenities upgrades. Once this money is spent, it will be worth the exact same as a brand new building like in Example #1 (this is a stretch as in reality it would be worth a bit less). Since you are not taking on the heavy risk of development, you do not need the same level of return, and you feel that half of the developers 25% margin (12.5%) is a fair return. Based on this, you would be willing to pay ~$728k per unit.

Please note that the costs to reach stabilized value should include an amount to compensate for timing when appropriate. Many investors only use the straight hard costs / unit in their budget for renovation projects, but timing is a real cost I think many miss. In this example, if the in-place NOI is $12mm but it will take over 2 years to get to that $16mm stabilized NOI, that is roughly $6mm ($15k / unit) in additional timing costs ([$16mm-$12mm] x 1.5) if I use some quick heuristics.

Obviously this is quite punitive ($35k vs. $50k is a big difference) and you want to win deals, so it cannot often be fully factored in, but it should be something that is on your mind especially if it is possible that it may take a very long time to execute the business plan.

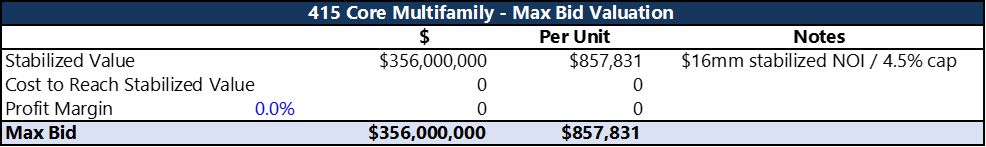

Example #3 – Core Multifamily Acquisition

This example represents the ultimate buyer of the end product in Examples #1 and #2. It is an institutional firm like a pension fund who is willing to pay top dollar for an incredible building. They know the market value is a 4.5% cap rate, that they do not need to spend any additional dollars, and that they do not need any additional return via profit margin because they are not taking on any additional risk. They meet the market and make the owners of #1 and #2 very happy.

Summary:

Real estate underwriting / valuation is not a complicated task and it is always best to keep things simple. Do not get lost in the intricacies of pretty models upfront, but rather use them as double checks later on. Every property can be broken down into its component parts: Stabilized Value, Cost to Reach Stabilized Value, and Profit Margin. Once you start thinking about deals in this manner, it will quickly become second nature for any opportunity you look at. I also guarantee it will make you more confident when analyzing properties or pitching them to your investors.