The Skinny:

Sizing a loan is a straightforward process driven by a series of “tests” but it is also a way for you to gauge and manage the risk of a deal.

Introduction:

The process for determining the proceeds for a CRE loan is fairly standardized no matter who the lender is. As noted in the debt is good post, the main criteria can be distilled into two categories, cushion and coverage. The objective for the lender is to provide as much proceeds within reason (so they can make more $ and meet their quotas) within a clear risk level (so the loan does not blow up and to avoid looking like idiots). Lenders accomplish this by running the numbers through a series of “tests” and usually take the minimum result as a starting point. The final proceeds and terms will be the result of negotiations and a further review of the borrower and the circumstances.

The Required Inputs:

To complete these calculations, you need the 4 inputs of purchase price, NOI, interest rate, and amortization period as well as your sizing constraints for each of the 3 main calculations of maximum leverage, minimum DSCR, and minimum debt yield.

Purchase Price / Basis – pretty self-explanatory, this is just the price you are paying for the property plus any revenue-enhancing capital expenditures. It is obviously the main component of the leverage sizing calculation.

Net Operating Income – this is the key component of the DSCR and debt yield calculations. This reflects the cash that the property is expected to produce before debt service. While not a fully accurate definition (since capex is not included), NOI in this context is a proxy for the “cash flow available for debt service” (CFADS). Note that this NOI is today’s amount, not some projected pro forma amount. Lenders can really only underwrite what is “known” and will rarely fully underwrite something that is speculative. The NOI they use for sizing will be based on the current rent roll and recent operating statements with some standardized adjustments.

Interest Rate – this is the most important number for the lender as it reflects their rate of return and implicit risk level. It also flows directly into the DSCR calculation because the DSCR is just a spread that the NOI must meet, so if the interest rate is higher, debt service is higher, which reduces the loan proceeds to offset the debt service (since NOI is the constant). Different leverage levels (e.g. 50% vs. 70%) warrant different interest rates to account for the risk, so lenders provide a “matrix” of what their target rates are for each leverage level, putting it back to the investor to decide what makes the most sense for their own risk / return objectives.

Amortization Period – this is the other component in the debt service calculation. Most loans require monthly principal repayments in addition to the interest expense. This benefits the investor by reducing their debt load and building equity, which also benefits the lender by reducing their own credit risk. Amortization derives from the latin root “admortire,” which means “to kill.” Although this is a little dark, it makes sense because this process refers to the killing down of the debt balance. The typical amortization period is 30 years, which means that if the loan term were 30 years, there would be no more debt to repay at maturity. However, since most loans do not exceed 10 years, there will be a “balloon” payment to pay at maturity for the remaining balance that can only be completed via sale or refinancing. Just like with the interest rate, the lender will offer different options. In exchange for a higher interest rate, they may offer “interest only” periods where the incremental repayments are deferred or excluded entirely, which boosts investor cash flow yields but does nothing to reduce the absolute debt level. Again, this is up to the investor to decide what works best for their objectives (most investors like to minimize their debt service to maximize cash flow, so interest only is usually one of their first asks).

Sizing Metric #1 – Leverage:

This is the most straightforward and arguably the most important out of the three main sizing calculations. Put simply, lenders require that investors have skin in the game in order to align interests and to provide some margin of safety. People behave differently when their own money is at stake versus other people’s money. Unlike a primary home residence, commercial lenders will rarely lend at more than an 80% leverage, so the minimum down payment or “equity cushion” is at minimum 20%. Most loans fall in the 50%-70% range.

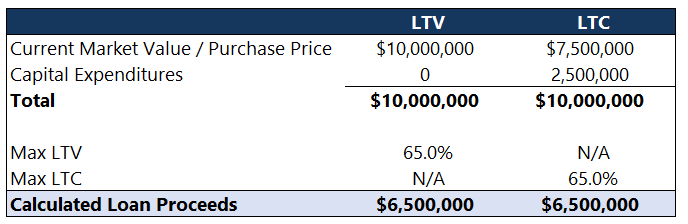

Leverage comes in two different flavors, loan-to-cost (LTC) and loan-to-value (LTV). LTC is typically used when there is a significant level of capital expenditures, while LTV is used when there is really not much additional capital involved. Developments and value-add projects will often be quoted with LTC because the current market value is not relevant, making LTV less applicable. The lender protects itself by pricing to the cost, even though the newly renovated product’s market value could be a lot higher upon completion. Again, lenders prefer to underwrite to what is known, and cost is more certain than a future valuation.

LTC Proceeds = Max LTC * (Current Value + Capex)

LTV on the other hand is used when a property is already in good shape since the market value is more relevant. The market value can be verified with an actual purchase price or solid comparable sales data. Sometimes a metric called loan-to-purchase price (LTPP) is used. Technically you could also use LTC here but it is a little superfluous since the cost just equals the purchase price. Using value is much clearer.

LTV Proceeds = Max LTV * (Current Value)

A helpful way to think about the relationship between LTC and LTV is with a ground-up development. A development’s construction financing will be based on LTC since its current market value is just a pile of dirt and its future market value is a far-out guess (things can change drastically in the 2-4 years it takes to build). Once the building is completed however, a new lender (called a permanent lender) is able to use current market data at that time to determine its market value and provide a new loan based on LTV that pays off the LTC loan.

Market conditions dictate what kind of leverage lenders will be comfortable with. If there are several leading recession indicators present, they may want to keep loans at 50-55% (45-50% equity cushion) since values are expected to stall or decline. If a recession is over and the recovery in full bloom, leverage could jump up 60-75% (25%-40% equity cushion) as property values rise again.

Sizing Metric #2 – DSCR:

This is probably the most impactful calculation in the loan sizing process because it is such a key risk management tool for both the investor and the lender. I also like to emphasize this metric because it focuses on the asset’s cash flowing abilities itself, independent from the borrower. The DSCR test seeks to answer one simple question, which is: what is the largest loan that can be provided based on the asset’s inherent ability to generate income?

For the lender, it is all about the coverage. To feel covered, they want a spread of income (CFADS) to their required debt service payments, most commonly of 1.25x. So if debt service is $1, they need to see income (NOI) of $1.25. This provides the lender protection in case revenues decline and / or expenses shoot up. There are often strict covenants (agreements to hold a condition true) that require the borrower to keep that 1.25x cushion and if they do not, they trigger a default. Again, the NOI the lender uses is rarely speculative, it is based on verifiable income and expense data. If the NOI stinks today but it will be great in 2 years when you complete your business plan, the lender usually has to underwrite the stinker NOI for their sizing analysis.

To calculate the max proceeds using the DSCR test, you need to break out your financial calculator or an excel spreadsheet:

DSCR Proceeds = Solve for PV by inputting the following:

(i) loan term (ii) interest rate (iii) amortization period (iv) payment which equals the current NOI divided by the minimum DSCR

The results give you a max loan amount based solely on the property’s cash flow. The simple rule is that when rates are low, the max proceeds that result from this test are big and when rates are high, the max proceeds are far more tempered.

DSCR sizing proceeds can get out of hand in a low-interest rate environment. If the market cap in Case #1 was 5.0%, the property would be worth $25mm and the LTV of the calculated loan would be a whopping ~85%! As we will demonstrate later on, it is important to keep this calculation in check via the other tests.

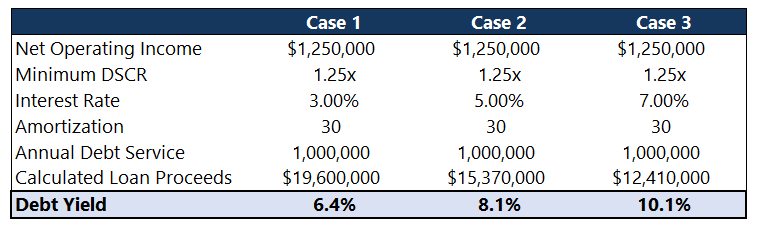

Sizing Metric #3 – Debt Yield:

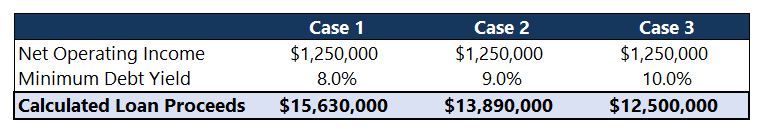

Debt yield is an increasingly preferred metric for many lenders because it is simple and is supposed to be independent of cap rates, interest rates, and other market forces. Said differently, the target debt yield is not supposed to change much throughout the cycle and is supposed to remain in a reliable range like 8-10%. The debt yield is simply the NOI divided by the loan amount, so it is related to the cap rate. You can think of the debt yield as the lender’s rate of return if the owner goes bankrupt and hands the keys to the lender. Their all-in basis / capitalization is simply the loan amount and their debt yield and cap rate become one in the same. Just like with a cap rate, the higher the better. A higher debt yield reflects lower risk and more comfort for the lender.

Debt Yield = NOI / Loan Amount

Debt Yield Proceeds = NOI / Minimum Debt Yield

Once again, lenders really prefer to use the verifiable in-place NOI for this calculation. However, for the debt yield they might size the loan on both an “as-is” basis and “stabilized” basis. Let’s say their plain vanilla target debt yield is 8%. If there is strong conviction in a deal that the stabilized debt yield can quickly reach 10%+, they might relax the in-place sizing threshold to say 6%.

While they are two separate calculations, there is a mathematical relationship between debt yield and DSCR. In fact, in my financial models I use this relationship to determine the future proceeds for a refinancing in the future because I like how it captures two sizing metrics in one, which allows me to quickly sanity check it.

Debt Yield = Loan Constant * Target DSCR

The loan constant is simply the total debt service payment (interest and principal) divided by the loan amount. Can you calculate the debt yields using the DSCR example in the previous section?

Once again it is evident in case #1 that low interest rates cause the DSCR sizing metric to be too thin. A lender with a firm debt yield floor of 8.0% would keep that number in check.

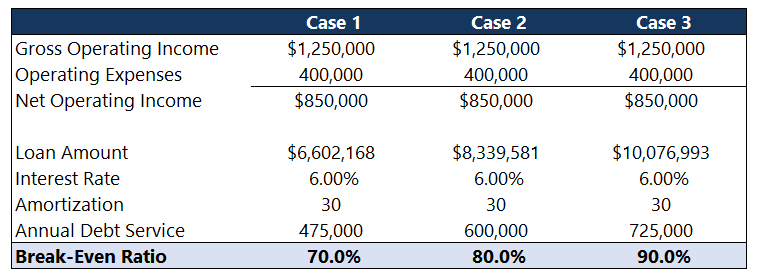

Bonus Method – Break-Even Ratio:

While it is not really explicitly cited in lender term sheets, the break-even ratio (BER) is my favorite metric to use, because it clearly captures in one number the true safety margin of a deal from both the investor and lender perspectives. It simply pits total revenues against total required cash outflows (operating expenses and debt service) to determine how bad a business plan can go wrong before you fail to meet those obligations. It represents the decrease in revenues (via some combination of lower rents and occupancy) that will set the deal’s cash flow to zero.

Break-Even Ratio = (Operating Expenses + Debt Service) / Gross Potential Income

So if your operating expenses are $400k and debt service is $600k, your required cash outflows are $1mm. If your gross potential income is $1.25mm then the BER is $1/$1.25 =80%. You know the GPI and Opex straight away but Debt Service is the “plug” that you will need to use in excel or your financial calculator to arrive at a PV that meets the BER threshold.

Lenders generally like to see a BER of 85% or less (the lower the BER the better!) but 75-80% or even lower is really where you want to be because it gives you so much more room if operations do not go the way you expected. I personally would not be comfortable knowing at just a 10-15% vacancy rate I will not be able to cover my obligations!

This is a bit of a circular process because in order to determine the loan proceeds that meet the target BER, you need to know what the loan terms are. But the loan terms are predicated on what the BER and its related metrics are. For this reason, I would recommend using BER less as a sizing tool and more of a risk checking tool once you have the traditional sizing analysis done. I would highly recommend you make BER one of your best friends as a real estate investor.

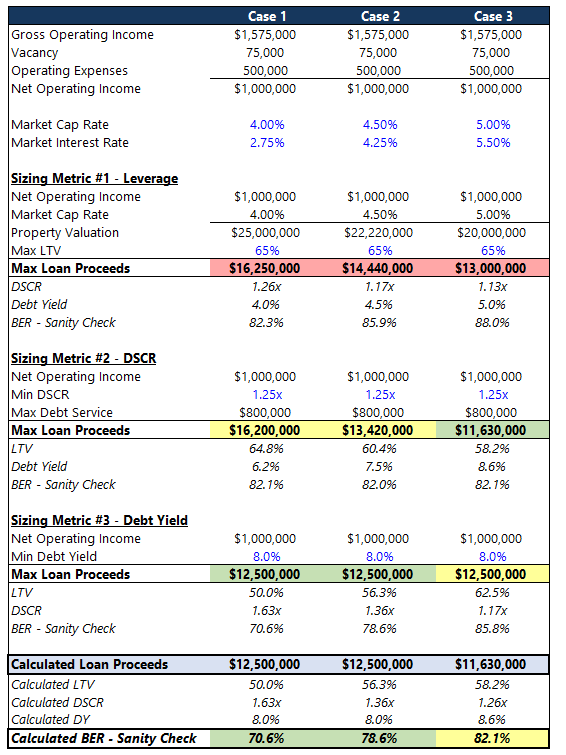

Sizing Analysis Example:

These various methods keep each other in check, especially in different interest rate and economic environments. LTV and DSCR in particular are susceptible to being distorted by frothy markets. For example, if the real estate world (including lenders) greatly overvalue your property due to a bull run, LTV is a dangerous metric to rely on. Similarly, if rates are super low, DSCR is not an appropriate way to size the deal either. Check out the sizing analysis below for three different economic environments to see how the metrics keep each other in check. Case #1 reflects a deal in the throes of the ultra-low interest rate environment of 2010-2022. Case #3 reflects the tightened environment of 2023. Case #2 reflects the middleground. For comparative purposes operations, amortization, and sizing thresholds have been held constant.

There are probably a few takeaways that immediately jump out. First, it is mostly the DSCR and debt yield keeping the LTV sizing calculation in check. Second, the debt yield is the strictest in lower interest rate environments. This makes sense and is why risk-conscious lenders like to lean on it, because it ignores market valuations and interest rates.

You also might be wondering why the calculated leverages are so low when you hear about your friends getting 75% leverage on their Class B/C multifamily properties. In this example, it is because of the cap rate to interest rate spread. These cases are based on my experience chasing deals in a major coastal gateway market, where the spreads are typically low or even negative (yikes!). If you have a nice juicy spread with the cap rate much higher than the interest rate, you will find that it is the LTV keeping the other metrics intact!

Finally, you can see how the BER varies based the different metrics. I view it as the great equalizer and is the first number I look at. Remember, keep this below 80% if you want to sleep well at night.

Summary:

The sizing process is straightforward and pretty much automated. Fully understanding each of these calculations will not only allow you to speak fluently to lenders but will also ensure that you do not fall prey to the allures of debt, which is the most dangerous double edged sword in real estate. Determine your own risk levels, with an emphasis on BER, and then faithfully apply them to your deals to best protect yourself in downside cases.