The Skinny:

Debt is what allows real estate to be the most effective way of both increasing and destroying wealth, so it is vital to understand how to use it judiciously.

Why Real Estate Debt is Good:

Using debt in your real estate investments has many benefits that allow you to be more efficient and effective in achieving your financial objectives:

Asset Purchasing Power – debt allows us to buy real estate that we do not really have the money for. While this may sound like a bad thing, when used carefully debt can be a very good thing. With just a 50% use of debt, purchasing power doubles. With 75% use of debt, purchasing power increases 4x! This allows individuals and companies to add big time line items to the asset section of their balance sheet, increasing portfolio sizes and gross wealth. While it may sound corny, I firmly believe there are real positive psychological benefits to increasing your asset base. Owning your own home instills a sense of freedom and pride. Buying an investment property or a small business, both of which use debt financing, instills a sense of ambition and stewardship to earn a rate of return sufficient enough to provide your family a better life.

Liability Reduction – while juicing your asset line items is fun and all, you will initially have to add greatly to your liabilities section to do so. Liabilities are generally not a good thing. However, real estate is different. In almost all instances, if you are receiving a loan, that means that there must be a clear path to a reduction of the liability. A reduction can be a literal reduction, meaning the debt is paid off, or a relative reduction, meaning the asset value is grown so that the equity cushion / margin of safety increases. What makes real estate so special is that aside from short-term aberrations, values trend upward in the long-run. Typical homeowners reduce their liability over time through home appreciation and by paying down their mortgage principal each month via amortization. Real estate investors reduce their liability not only through pervasive appreciation (just like homeowners), but also through intentional value-creation by improving a building’s quality and income stream. Student loans, car loans, and credit card bills do not enjoy this asset appreciation dynamic. With rising asset values and liability reductions, net worth can be increased quickly. This is why the average net worth of a homeowner is 40x the amount of non-homeowners, and is why real estate is objectively the most effective way to increase ones net worth.

Enhanced Return Potential – a more sinister sounding name for debt is leverage, which by its original definition simply means to amplify a force. A seesaw (the most benign example of leverage) can allow you to lift someone on the other side who is much heavier than you, but it could also cause you to go flying across the playground if you are not controlled and careful when doing so. While it is a double-edged sword, real estate is well suited for this amplification. Why? Well, real estate is inherently a good investment, especially housing. Everyone needs a place to live and shelter is therefore a non-discretionary need with a permanent demand pool. This means it is not very risky and lenders will not require a large risk premium to lend on it. Despite this lower risk, real estate’s innate return potential is very strong. While the historical rate of return for the S+P 500 is ~8-10%, most real estate investments have the potential to comfortably earn 10-15%+. With a high return floor and a low cost of debt, returns can be safely amplified. Keep this formula in your back pocket if you want to check for yourself how debt can enhance returns:

Levered Return = Unlevered Return + (Debt / Equity)*(Unlevered Return – Cost of Debt)

As an example, assume a $1mm purchase price, a 10% unlevered return, 75%/25% debt/equity ratio, and a 6% cost of debt

Levered Return = 10% + (75% / 25%)*(10% – 6%) = 22%! Wow, a 2.2x amplification. Powerful stuff.

Forced Savings Mechanism – this may sound counterintuitive, but real estate debt can be a powerful way to instill financial discipline. Most loans have an amortization component, which is an additional “cost”, made in addition to your monthly interest payment. These principal repayments reduce the balance on your loan, thereby reducing your debt liability each month. Interest goes directly into the pockets of the lender, it is of course how they make their money. Principal repayments, on the other hand, benefit YOU. It is a required or “forced” savings mechanism. Unlike your regular savings plan, it is non-negotiable and you cannot skip them. A lack of financial discipline, along with poor spending vs. savings habits, are some of the biggest financial issues plaguing our country. We are a consumption oriented economy and many citizens are unnecessarily fatalist and constantly say things like “I can never afford a home, life is unfair, the boomers screwed us over blah blah” while they purchase $10 coffees to remedy their hangovers caused by late nights out that cost $250 each time. Amortization forces you to be disciplined. If you have $1,000 and you have been eyeing a $750 luxury item (aka the equivalent of setting your cash on fire) I simply do not trust most to be responsible enough to resist the temptation of consumption and to instead put the $750 into an appropriate investment account. However, if you have a required $500 mortgage payment coming up, that luxury item is not even an option for you! Your hand was forced and that is a good thing. It is the same reason why I highly recommend setting up non-negotiable savings sweeps. Paying down debt is an investment in and of itself and is a very good use of your money. The forced savings mechanism is a key part of why homeowners’ net worth is so massively outsized.

Valuable Capital Partner – you should view your lender as an ally and trustworthy partner. The relationship should never be viewed as malicious, awkward, or combative. If it is, you are using the wrong lender. Real estate lenders are (usually) not grubby loan sharks. These are investors in your deal and are investing in you as a creditor, operator, and more generally, as a person. It helps to frame them as just a more risk-averse equity investor of yours. They are on your side and you both have the same objective, which is to buy a successful investment property together. Even more importantly, they are a very valuable resource during the acquisition process as they will help you in your due diligence to spot issues. Most lenders are experts in sniffing out BS and are trained to look for inconsistencies and issues with the physical property, its financials, and the seller. While they should not be solely relied upon, they are another member of your team who are all working towards making sure the deal is as advertised, so that you can all execute the business plan properly. You often hear the phrase “relationship lender” in the real estate space. This is a real thing. After repeated success, your relationship could mean better pricing and more agreeable terms moving forward, which in turn leads to a virtuous cycle with a long-term trustworthy capital partner.

Uncle Sam – the U.S. government loves real estate and loves debt (as evidenced by the ballooning U.S. debt spending!) and they like to show it with the tax benefits. Interest payments are tax deductible and reduce your taxable income reducing your tax burden. If you are like most individuals and want to minimize the amount of taxes you owe each year, this is a common and effective means of doing so.

How Debt Terms Are Determined:

For real estate investments, proceeds and pricing are determined by a multitude of factors such as location, property type, amount, term, creditworthiness, and of course broader market conditions. You can google something like the 5 C’s of credit for the typical standards. However, I would argue that it can be distilled into two key words, coverage and cushion, because these two words capture the essence of a lender’s primary objective, which is risk management. Remember, debt lenders do not share in the upside of an investment as their terms are fixed, so it makes sense that their focus is on downside risk mitigation.

Coverage – refers to what kind of monthly debt payments the property can support in the time between the loan commencement and the loan maturity. It is expressed using the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (“DSCR”) which is the ratio of the net operating income and the debt service. NOI is used as a proxy for the cash flow available for debt service (“CFADS”) although this is a bit flawed because it does not include capex! EBITDA in the equities world suffers from the same shortfall.

I really like to emphasize coverage because it focuses on the asset itself and distinguishes it from its creditor’s standing by seeing what kind of debt burden an asset can support when it stands on its own. Having a bulletproof recourse borrower with tons of cash on their balance sheet is great, but knowing the property can withstand stress and still pay the debt by itself is even better.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio = NOI / Debt Service

NOI is the lifeblood of the investment and shows what the property is earning today and projects what it will hope to earn in the future. Debt service comprises the interest expense and principal repayments, which are in turn driven by the interest rate and amortization period. A higher interest rate and shorter amortization period are stricter while a lower interest rate and longer amortization period are more manageable. Most lenders want to see a coverage of 1.25x or more so that if NOI drops, they still have runway to get paid.

Just like an equity investor, a lender’s return needs to be commensurate with the risk undertaken. If a property or location seems riskier, you would seek some combination of a higher interest rate, shorter amortization, and a larger coverage (maybe 1.35x) to arrive at the appropriate loan proceeds for the risk / return profile.

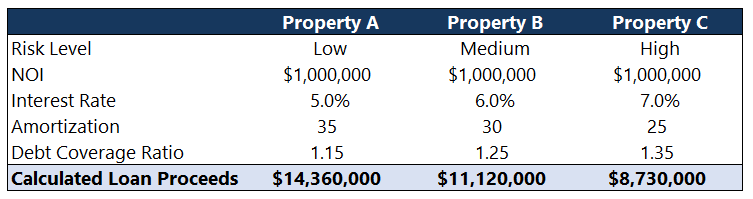

These terms have a big role on determining loan proceeds. There is process called “loan sizing” (described in more detail in this post) in which coverage plays a central role. It is a math equation in which you back into a loan amount using your trusty PV calculations from finance 101. You would enter the info you have (debt service, amortization period, and interest rate) and solve for the PV. Remember, the debt service input is simply the NOI / Coverage ratio. For Property A, this would be $1mm / 1.15 = $870k. Check out the chart below to see how different terms would determine the loan proceeds when you hold NOI constant.

The loan underwriter views Property C as much riskier and is requiring a higher interest rate, a shorter amortization period (aka a faster rate of principal repayment), and a larger margin of safety on the CFADS coverage. This results in proceeds that are ~40% lower than Property A.

Cushion – is related to coverage but while coverage is focused on the interim cash flow to pay the debt service, cushion is more focused on the margin of safety at the expected sale, when the loan would be repaid in full. When you hear cushion in this context, immediately think about the “equity cushion” which is the counterpart to the more commonly cited leverage amount (e.g. LTV – loan to value or LTC – loan to cost). If the leverage is 60%, the equity cushion is 40% and so on. The asset would need to deteriorate in value by a whopping 40% for a lender’s final repayment probability to be threatened. The confidence and comfort of maintaining or increasing this cushion is a key determinant in a loan’s terms.

If a lender is not super bullish on a geography or property type, they would want more cushion to protect themselves as this provides the leeway to be repaid if things do not go so well. The equity investor might get wiped out but the lender would still be fine. On the flip side, a lender might feel comfortable lending up to 90% of the cost of a project because the numbers so clearly show that the value upon a repositioning can be increased substantially. What a lender should really care about is what their cushion is at the exit. If a project costs $10mm all-in but it is clearly worth $15mm when the repositioning is completed, a $9mm / 90% LTC loan does not seem so scary because there is a high confidence that the true cushion will be 40% in the near future, not 10%. In fact, this is why appraisals can be kind of silly. If you are a genius who found a $20mm property selling for $10mm, you would likely not be able get a loan for more than $8mm because you need to show some skin in the game. But if the true value was used, you could get a conservative 50% loan and not put in a penny. This is not how it works in reality because you need to have some equity upfront to align interests, but it just shows how appraisals can be funny. It is often situations like this that allow for preferred equity and mezzanine lenders to hop into the capital stack at very high leverage points because of their comfort with the future value.

See the detailed post on how to complete a loan sizing to understand the actual mechanics and calculations for how lenders determine proceeds and pricing.

How to Protect Yourself from the Dangers of Debt

Debt can play a pivotal role in improving your wealth but it can also be your downfall. Using too much of it or simply having bad timing has led to the forced end of many enterprises for many centuries. How many times do you hear about crippling debt burdens at overzealous companies or real estate operators who are “overleveraged” and need to sell? Remember, you cannot go bankrupt without debt! The solution is simple, be careful, thoughtful, and selective in your use of debt. This does not mean to strictly use moderate leverage. It just means to meticulously review each deal to understand the inherent risks.

One of my favorite quotes in real estate and in life is that “pigs get fat and hogs get slaughtered”. I would highly recommend applying this mentality to your financing decisions as well. You should be paranoid and ask yourself “how can this decision hurt me?”. The best part about asking this question is that you can pretty much answer it yourself with some analyses. Here are some best practices to manage your risk level so that you can select a capital structure that protects you and your investors from getting hurt:

Embrace Temperance – only borrow what you really need. Utilizing as much debt as possible is very tempting because it juices your returns. However, too many operators forget that it also increases your risk, sometimes to a danger zone. Run some cases that compare forecasted return versus a risk mitigation metric such as the break-even ratio. If you can comfortably meet your target returns with 60% leverage, do you really need 65% or 70%? View every deal in the context of a risk / return spectrum. If that extra 5% in leverage gives you a mouth-watering projected return but its at the expense of dangerously low margin of safety on your business plan, put it out of your mind because it is not worth it. You will not do a deal again with your investors if you provide a goose egg due to greed.

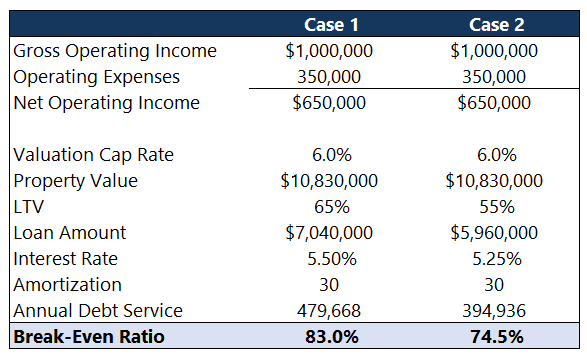

Emphasize the Break-Even Ratio – this is one of my favorite metrics for risk mitigation. Basically, you want to figure out how badly things can go on the income side before you can no longer meet your obligations on the expense side (opex + debt service). For this metric, the lower the better! The two main drivers on the income side are occupancy and rents. I generally like to emphasize occupancy for office / retail properties (since rents can be pretty locked in due to longer leases, but vacancy can be a lingering problem) and rents for multifamily properties (since every residential unit will rent for a certain price). A good heuristic is to avoid deals with a break-even ratio above 75-80%. Here is what that analysis looks like:

Break-Even Ratio (BER) = (Operating Expenses + Debt Service) / Gross Operating Income

Let’s review an example of how using the BER can help you make smart financing decisions:

In Case 1, the BER is a bit too elevated for comfort ($350k + ~$480k) / $1mm = 83%. So you work with the lender to re-run the terms at a lower leverage point like 55%. In exchange for the lower proceeds, you are granted a lower interest rate due to the lower risk. These changes reduce your BER to a much healthier ~75%. This means that through some combination of occupancy and rent decreases, you have a 25% cushion to meet all financial obligations and that will certainly help you sleep at night.

Note that even in Case 1, the DSCR is healthy for the lender at 1.36x ($650k / ~$480k) so this loan would likely get approved fairly easily. However, just because you can get it does not mean you should take it. Again, these decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis with the deal traits driving the call. If there are realistic scenarios that could torch your occupancy, go the conservative route. If it is a bulletproof deal with a massive margin of safety, go ahead and max out the leverage.

Sensitivity / Scenario / Stress Test Analysis – this is a fun and informative process in which you take each of the major deal levers (rents, occupancy, exit cap rate, expenses) and dial them down to increasingly unfortunate results. I generally like to start by moving each one independently to worst case situations and logging the results. Then I will combine the downsides to see what the “armageddon” case would be. If you are able to return your investor’s principal in an armageddon case (0% IRR / 1.0x) you should be very happy. While many operators stress these inputs down arbitrarily, I really recommend trying to keep them realistic. For example, if your rents are decreased by 20%, it is unlikely your occupancy will also decrease by 20% because they are at least partially offsetting (cheaper units attract more people). It is also fairly pointless to show negative 3% rent growth for 5 years straight or an exit cap rate that doubles (these do not happen in the real world). After you run 10 or more scenarios, you will have a very good understanding of what deal drivers can most easily sink you and where you can protect yourself accordingly. This process may even reveal unacceptable weaknesses in the business plan or flaws in the underwriting (hint: if a deal collapses because of a moderate increase in the exit cap rate, it is a bad deal!). A good heuristic to follow is to avoid deals where the realistic downside case provides <60% of your base case return. For example, if you are a value-add operator targeting a 15% IRR, a downside case return of 9.0% is reasonable. If you are a core operator targeting a 10% IRR, a downside case return of 6.0% is acceptable.

Think like a Lender – as mentioned earlier your lender is one of your investors, they just have a different return structure. To gauge the right level of debt for the deal, put yourself in the shoes of your lender and view the deal through their lens. Truly imagine yourself as a fiduciary for the insurance company or other beneficiaries that the real-life lender is responsible for. Combine this viewpoint with some of the stress testing in the previous step. Focus on the coverage and cushion in each scenario. Is the risk / return acceptable? What is the worst case realistic outcome? If you feel the terms offered by the real-life lender are not in alignment with your own assessment, you might have a problem and the terms may need to be adjusted.

Emergency Fund – I know it seems like a generic recommendation, but many operators do not have a sufficient emergency / rainy day fund for when things do not go to plan. It is easy to understand why, cash is literally a drag (on returns). If you call more money upfront to fund the rainy day reserve, those dollars start immediately accruing which negatively impacts the IRR. If you instead decide to fund the reserve incrementally by withholding some cash from the monthly or quarterly distributions, you might miss your original yield targets due to the haircut. It is tempting to do neither in order to maximize returns and hope nothing bad happens. However, this is dangerous because investors hate capital calls more than anything. It often feels (whether it is justified or not) like a betrayal to what was indicated to them. Instead you should be transparent and reiterate that you are simply being a conservative steward of their money. Sure, returns may be reduced a bit but it is a heck of a lot better than not being prepared. Plus, if nothing goes wrong, this money is returned to them with outsized distributions later on, offsetting some of the “cash drag”. A good heuristic to follow is to keep a working capital / rainy fund equal to 3 months of opex and debt service. This will give you the flexibility to cover any near-term issues and then you can adjust future distributions / holdbacks as needed based on where operations are heading. Remember, it is always better to have this cash and not need it than to need it and not have it.

Summary:

Debt is a double edged sword. It has the power to greatly increase your cash flow and wealth but can also lead to financial ruin. Fortunately, you can mostly control which of the outcomes you will achieve. If you are able to judiciously use it and manage your risk properly, you can greatly tilt the odds that it will lead to the former and not the latter.